Fall is here! Leaves! Halloween! And I’m already sick to hell of pumpkin spice.

I must admit, I do have pumpkin spice lattes in the fall, and I enjoy them muchly. I like an occasional pumpkin spice milkshake. And some pumpkin spice beer is ok... not too disgusting. But after that it starts getting ridiculous, and suddenly pumpkin spice is seemingly in everything, from lasagna to eyedrops.

Really, it is best in pie. Pumpkin pie.

But, it is pumpkin spice season, so we at Korneff Audio are jumping on the bandwagon with our Pumpkin Spice Compressor, or PSC.

The PSC (also known as the Pawn Shop Comp) is a super versatile plug-in. It combines the punch of a FET style compressor, with a tube preamp section. And then on top of that, it has switchable tubes, resistors, transformers and transistors. The net result is something far beyond the simple sweetness of pumpkin spice, or the functionality of just a compressor. The PSC is like an entire spice cabinet of colors and flavors, and you can use it all over your tracks and mixes. Unlike a lot of plug-ins, there isn’t one thing it is particularly designed to do. It does everything, although we’ve not tested it with lasagna.

So, here are three “recipes” from the Korneff Audio Kitchen, for applying the PSC to your recordings. They’ll give you some insight into the ways the Pawn Shop can add magic to tracks, and hopefully stimulate your own thinking and creativity.

1) Use a PSC to Help Track Things Quickly

When I’m tracking parts to develop ideas, I want to get things recorded as quickly as possible. However, if I’m moving fast, chances are I’m playing or singing a bit on the sloppy side, mic positions and technique are a bit loose, and instrument sounds aren’t fully worked out. Consequently, levels can be all over the place and the sonics can be off enough that things get lost in the mix, or become too dominant and distracting. I don’t want to slow my workflow down by adding EQ’s and compressors, and then fiddle with settings, but I do need quick control over things. Enter the PSC.

As I track, each new channel has a PSC instance on it. If I need a little compression, I press Auto Makeup Gain, turn up the Ratio a smidge and then pull down the Threshold ’til the meter bounces a bit. The initial settings for Attack and Release are usually fine. If a track needs bottom or brightening, or if it’s muddy, I go to the Back Panel and use the Focus and Weight controls to get it to fit into the mix so I can evaluate how the part works. These are not full featured EQs, but their frequencies are carefully chosen and effective for making the sorts of fast changes I want in this situation. The last thing I want to do is sweep through frequencies, dick around with bandwidth, etc. With the PSC, there’s just two gain knobs and four frequencies, and that’s enough for quick fixes.

The PSC also has considerable saturation capabilities, so if I want to experiment with distorted, overdriven vocals, or see what fuzz on the bass might sound like, I don’t have to add a saturation plug-in, I just mess around with the Pawn Shop’s Preamp Gain and Bias. With just those two controls, I can dial in anything from some subtle overtones to full out stomp box.

Once I finish my “idea” tracking, I can re-record things more carefully, or, if a track is close enough, I can add other plug-ins to more precisely take the sound to where it needs to be. In many cases, though, the PSC stays in the signal path because it adds character and a subtle vintage “something” to any signal you pass through it.

2) Operating Level Control = Secret Spice Mojo

This is my favorite knob on the PSC. It’s sort of a limiter that overloads and adds some saturation and harmonics, but who cares how it does its Mojo, the point is using that Mojo.

At low settings, from 2 to 6dB, the Operating Level Control pulls whatever you send through it forwards in the mix: things get a little louder, and seem to sit a bit more securely. I use it strategically to focus attention on things in the mix that have to stand out—lead vocals, instrumental solos, key melodic ideas, etc. I tend to add a few dB of it on snares, to give them more “size” in the mix.

At high settings, Operating Level absolutely squashes things, and because it has a very fast release, it adds a strange “pumping” sort of distortion that sounds like bad radio reception or something.

I use Operating Level SPARINGLY—I don’t slop it all over my tracks like, well, the way people slop pumpkin spice all over during the fall. Another way to approach it: listen to your mix. Are you losing any one particular instrument or part? Use Operating Level on that. In fact, I’ve added an instance or two of the PSC and ONLY used the Operating Level Control on a few occasions. 3dB of it adds so much.

3) Divide and Conquer the Bass Recipe

Getting bass to sit right in a mix is often a pain in the ass. You typically want bass big on the bottom, but it can interfere with the kick, and it needs midrange articulation otherwise it gets muddy, but you don’t want it to sound all clicky and “fingery.” It has to sound good on big speakers, and it also has to be present on an iPhone speaker. And bass is difficult to record well, especially when you’re not dealing with a great player who has a great instrument.

Here’s a bass fix recipe that almost always works.

A: Copy the bass track to another channel, or if you’re using multiple tracks, set things up so that you have the same bass parts in two subgroups. You basically need two bass tracks in parallel to make this work.

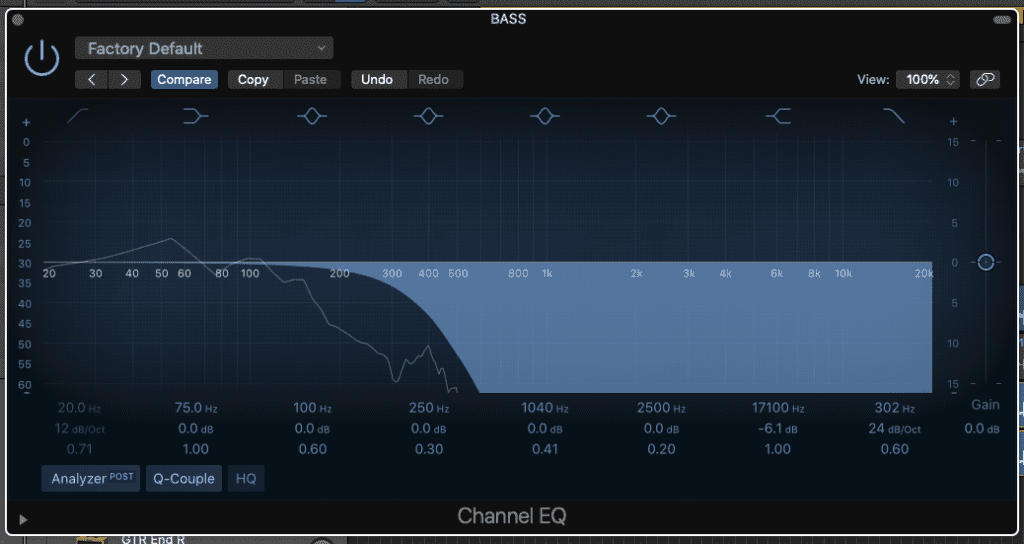

B: Stick a Low Pass filter on the first bass channel and roll off everything above 300Hz. I use a pretty steep slope, like 24dB/octave. On the second bass track, use a High Pass filter and roll off everything under 300Hz with the same, steep slope. So, now you have the lows of the bass on one channel, and the mids and highs on another.

C: Put a PSC on each bass channel after the filter. Now you can process each frequency range independently of the other.

D: On the low bass channel, I use the PSC’s compressor to control the overall boominess and low end sustain on the bass. I set the ratio really high - like 20:1. The compressor’s release is the critical control here. Longer releases will keep the bass more under control and cut down how long it hangs around in the mix, while faster settings can give lows a lot of blossom and sustain. On the back panel, I usually switch the Transformer to Iron, which sounds slow and laggy to me, and that accentuates the bottom. On the lows channel, I’m looking to get a thick, soggy sound—like the goop in a pie mixing with the crust to turn it into a kind of sweet pudding.

E: On the other mid highs channel, I set the ratio to around 8:1 and experiment with attack and release to get the amount of articulation I want. Generally, this bass channel will have a slower attack setting on the PSC to bring out the initial “pluck” of a note, and a fairly fast release to keep things lively and jumpy. I set the Transformer to Nickel on this channel, as it imparts a nice crispness to the transients. On the mid high channel I want the sound to have a bite, like when you chomp into a nice, fresh apple.

Because I have independent control of the lows and mid-highs, I can add saturation using the PSC’s preamp controls to the mid-high channel to get additional character and harmonics, while not losing the tightness of the lows. I can also add effects like flanging or reverb to the mid-highs without making the low end loose and unfocused. If I want huge, thick low end I can get that too without ever losing the articulation and “cut” of the bass in the mix. In the final mix I can also ride the two different faders to easily adjust the way the bass sits in the mix.

And, of course, this technique isn’t limited to electric bass, it works on synth patches, as well as guitars and vocals.

Not Just for the Fall

I never know how to end these things... but in summation, the PSC, unlike pumpkin spice, is not just reserved for this one season. And it’s not just useful for one application. It can be an integral part of your workflow throughout the entire year, helping you to work fast and still get great sounding recordings.