The Chart and EQ’ing Ideas

This is a running collection of EQing ideas—not so much recipes as quick thoughts on a particular application. Some of the ideas don’t involve EQs but other things, such as oscillators, etc.

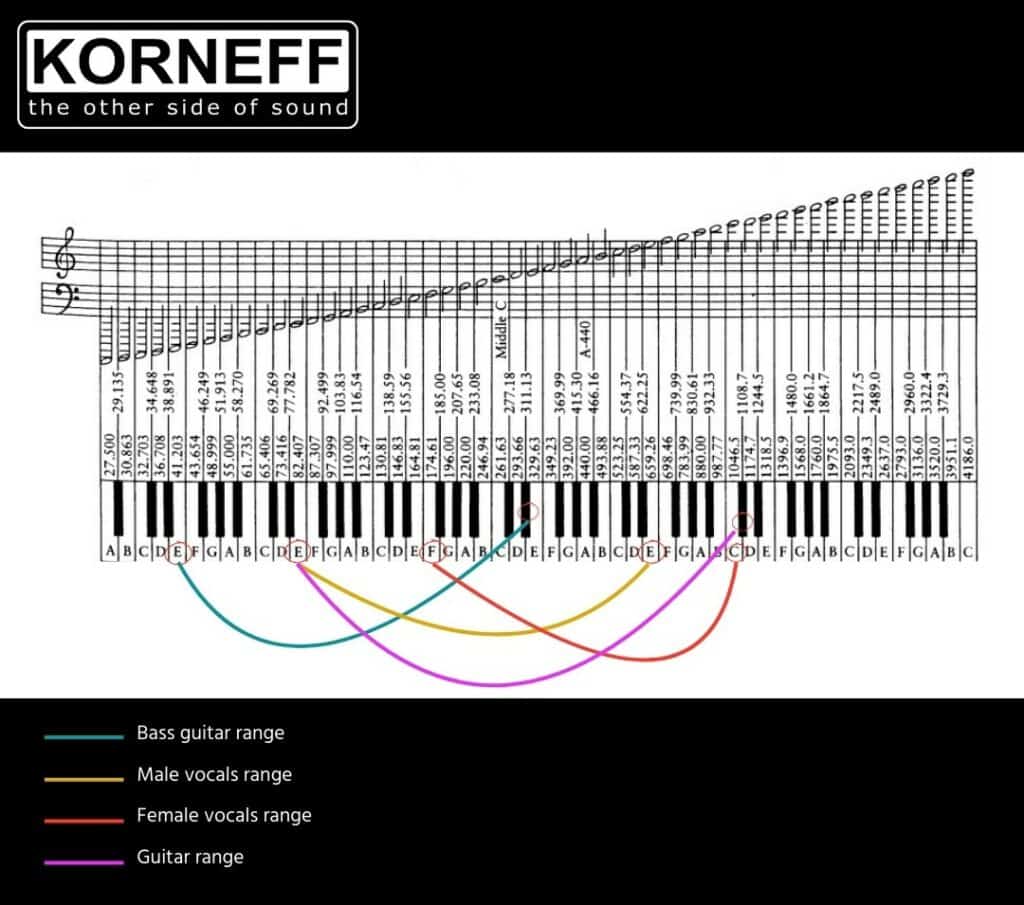

All of this, though, comes from thinking about instrument overtones, or harmonics. The pitch/frequency chart, and some knowledge of the math involved in the musicality of sounds, are part of understanding this stuff.

Click on the chart to download it.

The pitch/frequency chart is very useful but you can use your ears and get similar results. Also, digital EQs on DAWs feature frequency response displays so you can visually do a lot of this, but knowing some of the math behind it all will make you that much more dangerous in the studio, whether you’re behind the board or in the box.

The Overtone Series

The overtone series of an instrument determines its timbre, or how it sounds in terms of its frequency response. Most instruments play a sort of invisible, very quiet chord of overtones with each individual note. Simple things like flutes don’t generate a lot of overtones, but instruments like pianos and guitars dump out tons. These overtones are also referred to as harmonics, and the two terms are interchangeable.

A single piano note tends to generate octaves above the root very loudly, the fifth fairly loudly and the third somewhat quieter. In essence, a single piano note plays a major chord.

You can clean things up by notching out lower harmonics, remove harshness by notching high harmonics, or increase clarity by boosting the upper harmonics.

An example of how this might work

Let’s say you’ve got a musical part going from B (123Hz) to a G above it (196Hz). Doubling things, there’s octave gook or whatnot from 250Hz to 400Hz, and then more of that the next octave up— from 500Hz to 800Hz.

There’s also overtones from the fifth. To figure out the fifth, multiply the B (123Hz) by 1.5 to get 184Hz. But if you know some basic music theory, just use the chart. The fifth of B is F# (184Hz), the fifth of the G is D (293Hz), so the range of fifth gunk is from 184Hz to 293Hz, and then there’s the fifth an octave above that at around 370Hz to around 400Hz.

From looking at the numbers, there does appear to be stuff building up in that 300 to 700 range. How often have you done cuts in there to clean things up? Guess why: that’s where a ton of overtones tend to accumulate.

Do the frequency choices on a Neve 1081 EQ make more sense now?

Pass Filter Magic

Using high pass filters, if the song is in A, you can set the frequency at 110Hz and get rid of everything below that, unless there’s a lower E involved, in which case the cut-off frequency is at 82Hz. What if you automated the frequency of the high pass to match up to the lowest note of a chord? Would that clean up the bottom end a lot?

Tune the Drums

Match the toms to specific pitches. Song in D major, crank up a bell-shaped boost at 146Hz, or whatever pitches you want that are part of the D major scale. How about tuning drums specifically to pitches?

Boost up the third to make a drum sound “Major.” Boost up the flat third to make it sound “minor."

Of course, you might try this and it sounds awful because most percussion instruments dump out a huge amount of enharmonic (frequencies not mathematically related to the fundamental).

Delete Resonant Notes

Recording a bass and one note BOOMS and triggers the compressor too much? Look up the note on the chart, notch it with a tight bandwidth at that frequency and then feed that EQ’s output into the compressor.

More Resonance Elimination

Acoustic instruments are designed to resonate. It’s a feature not a bug: the resonance functions as an amplifier. And it works well: compare the volume of an acoustic guitar to a solid body electric that’s not plugged in.

However, mic’d up close, as is typically done in the studio, that resonance can be too much. Remember, it’s designed to make the instrument sound good at a distance, not up close. So, often that resonance needs to be cut back to balance the instrument properly on a close mic. Of course, a lot of this you can do by moving the mic around, but you can also nip it out with an EQ.

I’ve done this mainly with guitars, drums and cabinets, but it works with anything that resonates, including speaker cabinets.

Mute the strings and tap the lower back lightly until you get a resonant “uuuuuu” sort of sound. Figure out the frequency using a mic plugged into an RTA. That resonant area will tend to get picked up by mics and add mud. Cutting in there tends to fix it up. In the old days, we’d cut that out before going to tape. It’s always good to get rid of stuff that you don’t want to deal with as early as possible.

You can bang around on instruments or cabinets or drums or cajons or really anything to figure out where the resonances are at. Cutting around that area almost always cleans things up a bit. I’ve fed white noise through speaker cabinets and looked at the output on an RTA to figure out the resonances.

Notch Not the Fundamental

If a note seems loud and you don’t want to hit the fundamental, notch out the octave and the fifth, or even the fifth above the octave. Note that our Insufferable Midrange Filter on the AIP has something like this happening in it—you can notch the frequency and an octave below and above.

Get Any Note to Feedback

Want a guitar to “hang” with feedback on a particular note, like this? Want to do it with total control and at a low volume so you don’t go deaf?

Get your guitar all set up. On the monitor channel, find the note you want to feedback on the chart and then boost that frequency by 10+ dB with a narrow bandwidth. Switch the EQ to bypass. Hit record. When it comes time to get the note to feedback, pop in the EQ and hear the note SCREAM. Voila - instant feedback. And because you put the EQ on the OUTPUT, you didn’t print any of it to a track, so it just sort of magically happens. And again, you can “tune” the feedback to any note or even a chord by looking it up on the chart.

Taming Drones

Some instruments have a lot of drone activity — bagpipes, sitars, certain keyboard patches, and the most common pain in the head, open-tuned guitars.

Open-tuned guitars drone principally because players come up with parts to take advantage of the open strings, but any part with ringing strings can make things muddy really quickly. So, if the tuning is an open G, there’s going to be a lot of G and D action happening. Narrow cuts at those frequencies can lessen some of the ring and drone. Or, reverse it to bring it out.

Harmonics on Synths

If, in a mix, a synth sound is too present, often one can adjust oscillators that are adding information (harmonics) above the fundamental. Turn that octave down to get the part to sit in there more nicely.

Alternatively, if a low synth part can’t be heard on a small speaker, like an iPhone speaker, and it’s important to hear that part better, increase the oscillator an octave up. Or, use an EQ to boost those frequencies an octave above the fundamental.

Harmonics on Low Kicks

Really low kicks and bass, that are down below 100Hz, probably won’t show up on a small speaker. I guarantee an iPhone doesn’t go down that low. But your ear can hear the overtones of the kick or bass and then “invent” the fundamental. You can help this process along by figuring out the fundamental of the kick and then reinforcing it by boosting two octaves above it.

Complementary Boosts and Cuts

You’ve got a female vocal that’s lost in the mix. You figure out that if you boost it down in the fundamental area, let’s say around 200Hz, and even more in presence region (10x 200 = 2kHz) you can get that vocal to sit there well. But it sounds harsh or somewhat odd because you’re boosting it a lot.

So, rather than using a lot of positive gain, boost it much less and cut other instruments that occupy the same frequency range in those same places, but not by a lot. Just a bit of negative gain. If the voice requires 8dB of gain at 2kHz to be heard, boost it 3dB and then cut whatever else is in there by 5dB at 2kHz. It’s like you’re making frequency puzzle pieces.

More to Come

here

As Dan and I think of things we’ll add it here. And if you have ideas, send them in and we’ll add them to this page, with your name as the contributor.