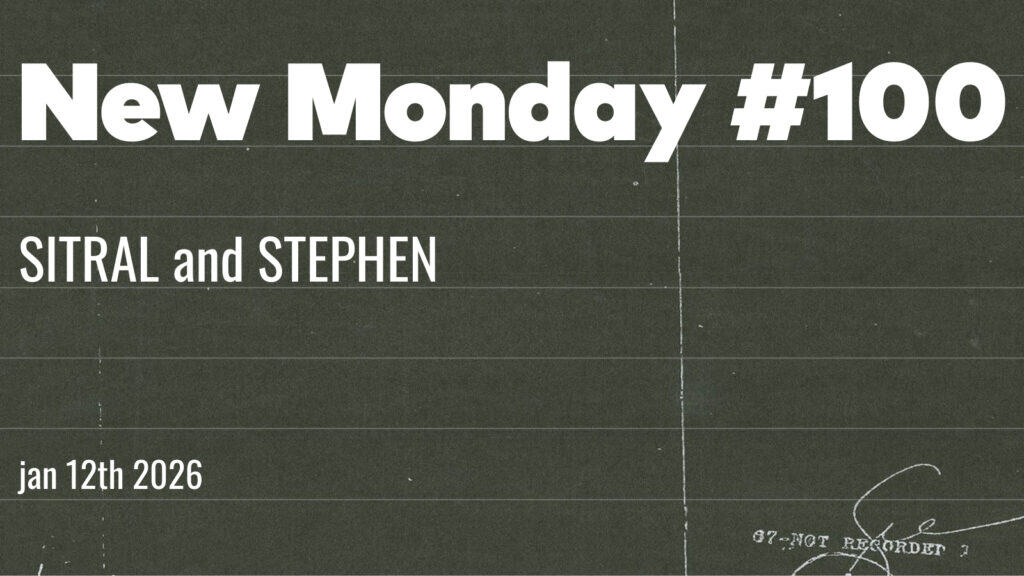

New Monday #100

Happy Monday!

Dan and I are always happy when we manage to get our shit together enough to put out a new plug-in. And we’re especially happy when it’s qualitatively really good and people like it and find it useful. So, I’m happy this morning with the SITRAL Klangfilter W295.

Check out the SITRAL Klangfilter W295 here.

It’s a good Monday.

The SITRAL STORY

I’ve been dropping hints, as I always do, for months about this plug-in. All of the articles on equalizer circuits were inspired by wanting to know more about the physics underneath what we were making, and to teach that.

For those of you who haven’t been reading along, the W295 is an active, inductor based EQ that uses transistors. The technology shift that moved the W295 out of broadcasting and into studios was the rise of cheaper, powerful integrated chips, and a circuit design that obviated the need for an inductor, the gyrator circuit. I’ll cover this in a few weeks.

The distinctive sweetness of the W295 is caused by design and the use of specific transformers and inductors, and particular transistors. All of these little elements contribute tiny percentages to the overall sound; they add tiny bits of harmonic distortion, tiny bits of slight changes to the wave form, and amazingly, our ear can hear these things.

That our SITRAL captures those nuances is completely Dan’s painstaking modeling, figuring out all of the math involved, and then coming up with a way to run that math in as close to real time as possible. The SITRAL Klangfilter W295 is a technical high watermark for us. In fact, and I hate saying something that sounds braggy, but at this moment, the SITRAL is perhaps the most "analog" digital plug-in out there. That doesn’t mean it will stay in that position, but I do look at it as the first step on a climb up yet another mountain.

Our particular journey to the W295 started over a year ago. Dan loved the sound of the hardware and wanted to re-create it. The original version of the plug-in was only a model of the W295b: high shelf, low shelf, midrange boost and cut. At a glance, this would appear to be the most useful version of the plug-in, and this is the one all the other plug-in developers have modeled. It is the most “modern“ version of the SITRAL in that it looks and functions the most like any EQ that one would find on a modern console.

Our first version sounded great—this is what Tchad Blake has been using for the past year without telling anybody. We were actually set to release it… and then Dan went back to the drawing board.

He decided to model the original W295, which had a peak only midrange, and the 295A which is a tilt EQ. We discovered that the sounds of all three models were different, and they all had their own unique uses. Both Dan and I use the original W205 more than we use the W295b, and we love the tilt EQ on the W205a. You need to try all three models. They're similar but not the same thing at all.

Dan also revamped the transformers and buffer amp. This iteration of the plug-in sounded amazing, but the interface was clunky and not intuitive. We spent a lot of time refining that interface to strike a balance between usability, tweakability, and clarity, while maintaining the flavor of the original hardware from the 1960s.

To be clear, we’re always looking to make our plug-ins as a reverse mullet: party upfront, business outback. But we are also looking to do something that I don’t think a lot of other plug-in companies are trying to do. We’re trying to design things that move you into a back-and-forth conversation with the creative work you’re doing.

What do I mean by this? Last week I wrote about Jimi Hendrix and The Wind Cries Mary. That song was knocked out in 20 minutes on four tracks. There were a ton of things beyond the control of everybody involved. There were not unlimited options. There were some decisions that you could make, and other decisions that were made for you that you just had to live with.

The conversation is something like this: I want to get a really cool drum sound. Studio mic locker says we only have five microphones and it all has to go onto one track. I want to add a whole bunch of guitar parts. Tape deck says you can’t do that and if you try it, you’re going to lose quality and you’re going to increase the amount of hiss, noise and saturation. I want to cut my vocal again because it’s a little out of pitch. Mr. clock says we have to mix now.

The analog recording process was a series of negotiations between the humans and the equipment, between the circumstances and the dreams. The process was also a series of negotiations between the members of the band, or with the producer.

Each negotiated outcome affects the next step of the process. You’ve sort of lost the kick drum on the one drum track, so maybe in the mix it’s EQ’d a certain way to get some of it back. Maybe the vocal isn’t perfect but there’s a certain charm to it. Or maybe you decide to double it to gloss things over, and that in and of itself becomes a unique moment on the recording. Or maybe the guitar player insists on doing something a certain way no matter what you say, and you don’t want to throw the dude out of the band. So you agree.

Both Dan and I prefer to use the stepped controls on the SITRAL over using the variable setting. It means sometimes I have to settle on a sound that isn't exactly what I want, but I decide it's good enough and let's move on. That choice will influence the next thing I do in a subtle way, as I work through the song and jump from decision to decision to decision.

For me, I want jumps, which are moments of giving up control. Moments where something unexpected could happen... where I might find a happy accident that’s better than anything I could’ve thought of or "controlled" into existence.

We’re looking to make plug-ins that lead you to happy accidents, so you can find something better than what is actually in your head. And we also want you to be able to get exactly what you have in your head. This is the conversation we are in with our plug-ins and our process to develop them. And this explains why our interfaces are quirky in the way they’re quirky, and why we do the things we do.

SITRAL is really a very happy accident that we’re glad we had.

I hope that makes sense. Feel free to write me if it doesn’t, or if it does. Conversation is what it’s all about.

STEPHEN SPENCER

It’s been a freaking crazy couple of weeks in the world and upsetting couple of weeks in the world. I found something on my feed that is really delightful.

Stephen Spencer takes the stories his three-year-old daughter tells him and turns them into lyrics, puts chords over them, and then records the whole thing and puts it on Instagram. You want to hear these things!

https://www.instagram.com/reel/DRQCOiCjAzf/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

Mr. Spencer is a music teacher at Hunter College, an expert on theory who’s writing his dissertation on “a novel approach to the analysis of timbre in modernist and contemporary music.” Heady stuff. I’m glad he throws some of that energy towards “Funchy the Winter Witch.“

https://www.instagram.com/reel/DSI64cgjf77/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

As a player and composer, the dude has chops. This guy really knows how to write music. Interesting chords, great melodies, and perfect crafting of the music to the rise and fall of the lyrics. This particular song's ending makes me cry:

https://www.instagram.com/reel/DSdVPTGjzcS/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

In this world, which is pitching back-and-forth between tearing itself apart and giving up its soul to AI, here’s this wonderful little moment, where you can have everything, and Santa always brings you everything. In 25 years, perhaps she’s getting married and Dad plays a bunch of these at the rehearsal dinner. How fabulous would that be? And wouldn’t you be the luckiest little girl in the world to have that dad?

Warm regards,

Luke

PS - Stephen Spencer has an album of music for grown-ups on Bandcamp. Much more of an emphasis on mood, texture and sound design. Good stuff!