What’s Special About the MDR

Reverb has been a studio staple effect since the 1950s, and traditionally, it’s been an expensive proposition. As an acoustic phenomena, reverb is complex and re-creating it required dedicated spaces initially—reverb chambers. Real estate ain’t cheap. Later, mechanical reverb simulators, like plate and spring reverbs were developed, but it was still costly. Digital reverbs started appearing in studios in the 80s, sounding great but again, rather expensive.

In the early 90s, the price barrier was broken and digital reverb units became affordable enough to find homes in smaller studios, home set-ups, and in musicians’ live setups. Soon artists were replicating their live and home studio sounds in the big studio by using these little cheap reverb units.

More expensive digital reverb units used a process called convolution to simulate reverb and other delay effects. Convolution required a lot of processing power, which made for an expensive and large unit.

An innovative designer named Keith Barr, trying to skirt this issue, developed a different means of generating reverb in part inspired by an older analog delay technology called “bucket brigade.”

Picture a bucket of water being handed from one person to another to another to another. That handoff takes a moment of time. The more people on the bucket bridge, the longer it takes the bucket to travel from start to finish.

This is roughly how a bucket brigade circuit works: a signal is passed from location to location within a circuit, or within a chipset. In the case of an analog bucket brigade, the signal quality degrades as it goes from location to location — think of water splashing out of the bucket as it’s passed.

Mr Barr did a similar thing but in the digital realm, using a computational loop. Think of the bucket perhaps being passed in a circle. The result wasn’t necessarily realistic, but it had a unique character, and for certain types of effects it was better sounding than convolution. Most importantly, it could be accomplished using less computational power, which resulted in low-cost, physically smaller devices. Instead of needing a dedicated room or a three-rack space box, you could get high-quality reverb out of a guitar pedal.

Mr Barr’s designs found their way into all sorts of processors and into the hands of musicians and engineers. The sound of many genres, such as Shoegaze and Trance, is built around these little, low-cost reverbs.

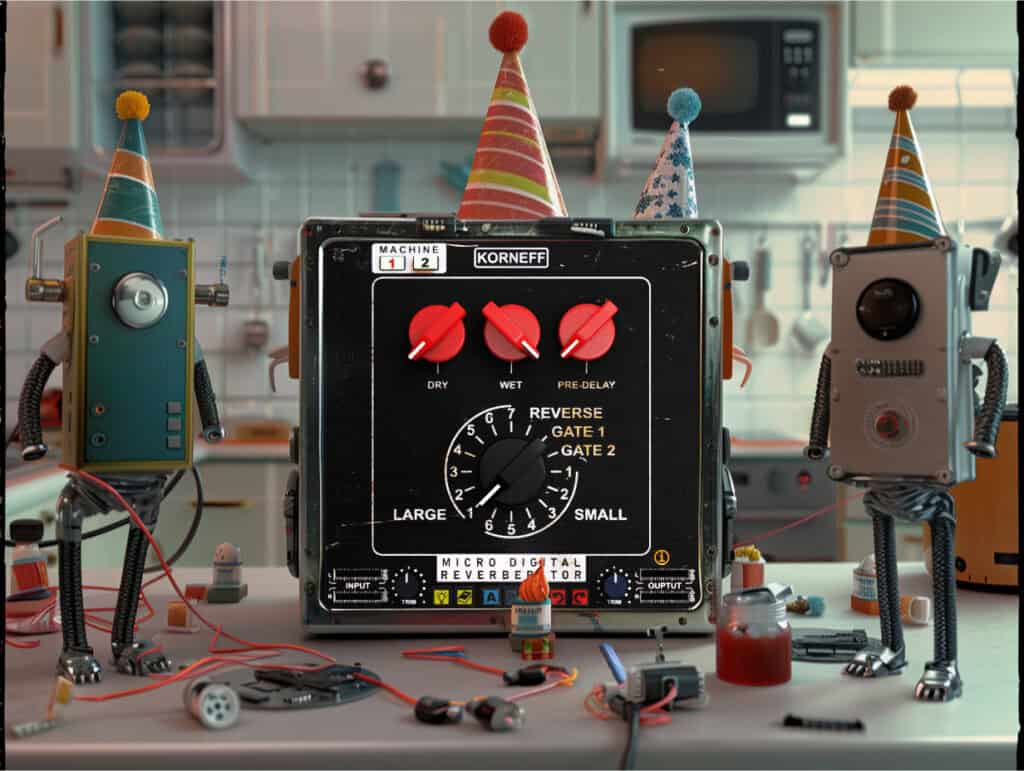

Our Micro Digital Reverberator is faithful to the sound of these units if not to the technology. Computational power is now cheap. Our MDR is built from carefully sampled impulse responses taken from our own collection of vintage hardware that we used in our home studios decades ago. It’s an interesting twist of fate that an inexpensive process, created to mimic an expensive process, is now itself being mimicked by the expensive process, which isn’t expensive anymore!

Whatever. The MDR has the sonic character of the original units and the fast, easy interfaces that made working with these things such a snap in the studio.

We use them the way we used them 30 years ago: slapping them onto a send and return, picking out a preset, and moving forward on the session with minimal fuss. Sometimes we’ll swap in something different in the final mix but more often than not, the unprepossessing Micro Digital Reverberator winds up being the reverb we use across the entire project. Fast, simple, and inexpensive has always been a winning formula.

Keith Barr died in 2010 at a relatively young 61. He was an innovator and a pioneer.