Audio 101 - Electric Fields, Magnetic Fields, and Inductors

Last week, we ran into electric fields. When electrons "push" a lot into the plate of a capacitor, an electric field is formed to store that energy, and then when the capacitor drains, that energy feeds back through the electrons and into the circuit.

These "pushes" we've been talking about... we've been thinking of them as a unit of energy. We've developed a mental picture of electrons passing a "push" along from one electron to the next. What that push really is, is an electric field pushing its way through the material.

In fact, the push doesn’t travel down the wire as electrons moving. The push travels as a wave in the electric field. The electrons barely move. The field is what moves.

It gets more bizarre: when the push travels through a wire, the energy isn’t even inside the wire. It’s not in the copper. It’s actually in the electric field around the wire and its insulation. The wire just guides the field, the way a track guides a train, but the energy rides outside the metal.

SO... when we have a circuit, we're moving and manipulating electric fields that travel around the circuit but kind of outside of it. It's hard to fathom. You can think of it as a push, or a message being sent from electron to electron, or as an electric field. Whatever helps you to see it in your head.

Now, when the electrons move the field along, they physically move a tiny tiny bit. They do this comparatively slowly—much slower than the speed at which the electric field travels. So, the electrons themselves aren't racing through the circuit. They're shuffling a little bit as they pass the field along.

But, when they shuffle, they create a tiny magnetic field. In fact, whenever you have an electric field passing through, causing electron shuffle, a magnetic field is generated. It is typically very weak to the point it's inconsequential.

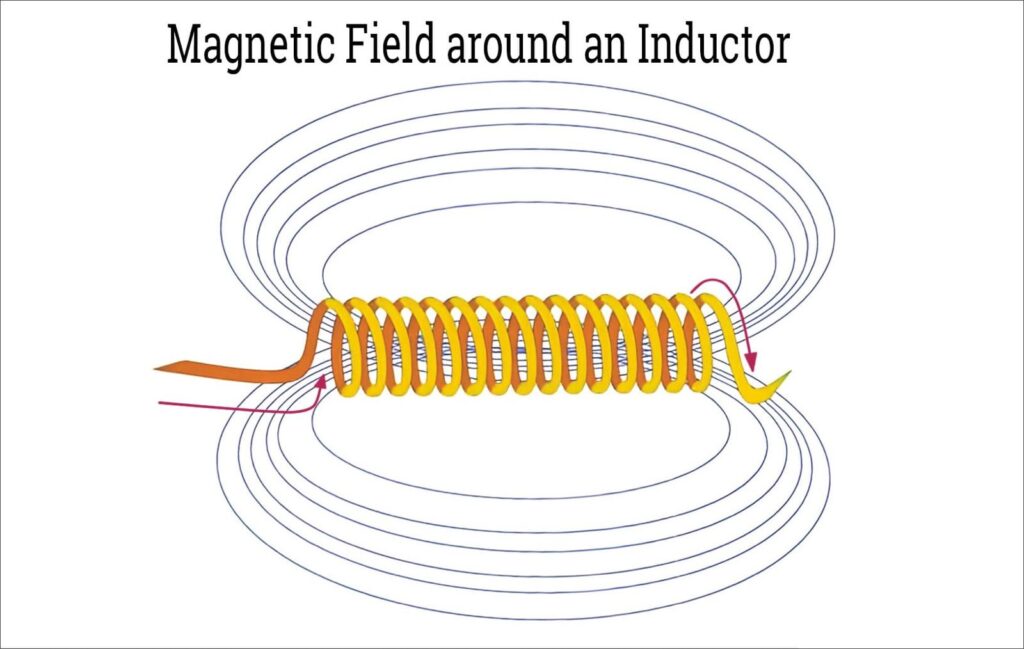

However, if you get a lot of electrons together, the magnetic field increases in power. How do you get a lot of electrons moving together? You use thicker materials—fatter wires—and then you wrap those wires into coils or shapes so that all those tiny magnetic fields add up. You cram as many electrons as possible into a given space and get them all wiggling in the same direction.

That's an inductor, isn't it? It's also, with some modifications, a transformer, or, with a lot of modifications, analog tape!

Inductors

We already know that an inductor is a coil of wire. And we already know that when we push on a bunch of electrons and keep switching the direction of the current — which is what alternating current does, and an audio signal is alternating current — the electrons find it difficult to switch from pushing in one direction to pushing in the other. That difficulty impedes the signal from passing through easily.

Let’s rephrase that.

When the electric field pushes into an inductor, it moves the electrons a tiny bit, and they generate a magnetic field. The stronger the electric field is — the bigger the push — the stronger the magnetic field becomes.

Now, electrons don’t have mass inertia in any meaningful way inside a conductor. They aren’t like cars trying to accelerate or slow down. Their actual drift speed, or physical movement, is incredibly slow. But the current — the organized movement of charge — has something very much like inertia. When you get a current going, it takes energy to change it. That “current inertia” lives in the magnetic field.

So when the electric field becomes less powerful, the electrons don’t instantly stop responding. The magnetic field collapses, and as it does, it pushes energy back into the electrons and keeps the current flowing a little longer. That’s why we say a magnetic field “stores energy.”

Now, when the electric field changes direction — because it's an alternating current — the electrons keep trying to push the way they were pushing, powered by the collapsing magnetic field. Only when that magnetic field is fully drained can they finally start pushing in the opposite direction. As they begin to move in the new direction, they generate a new magnetic field, opposite the old one. Every time the current tries to reverse direction, the magnetic field has to collapse first before the electrons can switch and build a new field.

All of this happens extremely fast — fast enough that you don’t see it happening — but it is still not as fast as the electric field itself travels. That lag has important consequences that we’ll cover later.

Back to our circuit with an inductor in it...

The faster the current tries to change direction, the less energy gets stored in the magnetic field. In other words:

High frequencies store less magnetic energy.

Low frequencies store more magnetic energy.

If there is a lot of magnetic energy stored up, that energy all has to drain before the electrons can push in a different direction. If less energy is stored, it's easier for the electrons to push in a different direction.

The result is that the inductor impedes low frequencies — it makes it harder for them to get around the circuit. Low frequencies spend too much time building big magnetic fields, and those magnetic fields push back hard.

At high frequencies, the inductor doesn't store much energy so it has less energy to push back, so high frequencies slip through the inductor and travel around the circuit more easily.

Do we need to recap all this?

Charge moves about a circuit as an electric field.

Capacitors store energy as an electric field, and they roll off the highs.

Inductors store energy as a magnetic field, and they roll off the lows.

Put them together and you get a bandpass filter.

Next week, we’ll talk about passive EQs.