An Old School Approach to Saturation

If you went back to a recording studio 30+ years ago, you wouldn’t encounter a piece of audio hardware called a Saturator. That wouldn’t be in any of the racks, nor would there be a knob or a switch labeled Saturation anywhere on the console. Fast forward to right now, saturators are everywhere, tucked into everything from compressors to EQs to dedicated saturators. All of our plug-ins have some sort of saturation capability, in some cases quite a bit.

Why no saturators back then? Why so many now?

The answer is that there was a TON of saturation happening back in the good old days, but it was spread out across the entire signal chain, from microphones to the speakers.

To recap: analog circuits have an operational "sweet spot.” It can be thought of as the signal level in which the waveform feeding out of the circuit is identical to the signal feeding into the circuit. This is called linearity. The sweet spot is where the circuit is at its most linear.

What does that look like? It means the waveform feeding in has identical peaks and valleys to the waveform feeding out.

But if you were to zoom in on that output waveform, you might see some very small differences compared to the input waveform. The peaks and valleys might have a slightly different curvature. The waveform might look a little bit distorted.

Which is because it is. Because no analog circuit is so perfect that it doesn’t leave its imprint on the waveform as it passes through it—all circuits add distortion. Now, that distortion might affect the envelope of the wave passing through, changing the distance between peaks and valleys, or it might change the phase of things ever so slightly, or it might add additional waveforms to the original waveform. These additional waveforms are usually incredibly low in power, inaudible. But they’re there, and they’re called Harmonic Distortion.

%THD and ears

When you look at equipment manuals and spec sheets, harmonic distortion is often listed as a percentage. %THD refers to the Total Harmonic Distortion being added by the circuit. Generally, the lower the THD, the better the piece of gear is, and the more expensive. Because getting the %THD low requires carefully designing and optimizing circuits, using precisely made components, keeping very high levels of production quality during the manufacturing process, and all that adds up to charging a higher price.

What %THD can a person hear? It depends on the frequency range, the person, and the distortion. A trained ear might be able to hear as low as .3%THD, but that might vary depending on the math of the harmonics being added—odd harmonics tend to be easier to detect than even (odd harmonics tend to be unpleasant). It’s also easier to hear harmonic distortion on high-frequency signals.

Gear gets too clean?

As integrated circuits came into use and manufacturing processes improved, the average %THD went down. Equipment went from colorful to very clean indeed by the mid-80s. SSL consoles had total harmonic distortion down around .02%THD. Compare that to Shure's Level-Loc, released in 1969, which had 3%THD, which Shure touted at the time as being incredibly low. UREi’s 1176 compressor, released in 1967, has .5%THD—lower than the Level-Loc but still noticeable to the average ear.

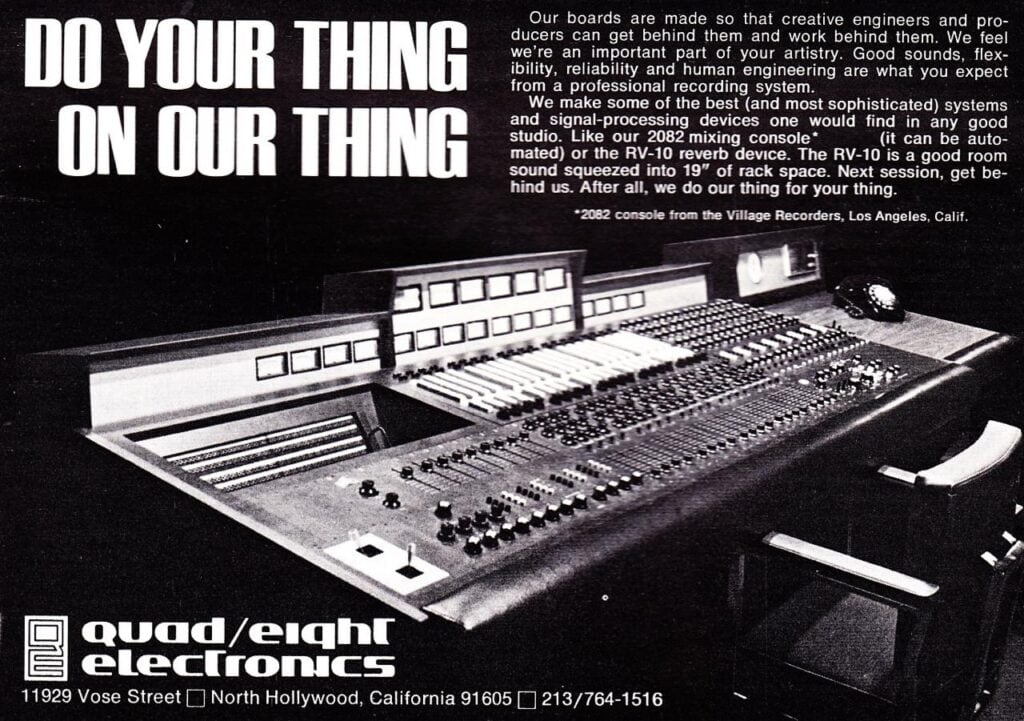

However, with an all-analog signal path, even very low amounts of harmonic distortion add up. The mic, the pre-amp, the outboard, the analog tape deck, the console, more outboard, and all of this stuff sprinkled heavily with transformers and transistors and tubes, all of which add a tiny bit of harmonic distortion. Multiply this by a bunch of channels. The result is really quite a bit of harmonic distortion, but it is spread out all over the studio and not concentrated in one or two pieces of equipment. Quite a bit of harmonic distortion is another name for saturation.

And, of course, our ears like that saturation. It sounds “warm” and “sparkly” and all sorts of other adjectives.

But consoles disappeared, magnetic tape disappeared, everything went into the box, and suddenly the only thing adding saturation to the recording was outboard mic pres, whatever outboard compressors or other processors might have in the home studio, and the analog side of the AD/DA converters involved. Things got too clean, so everyone started adding saturation as an option or as a specific product.

In the good old days, saturation was a bug. These days, it's a feature.

Saturation in our Plug-ins

All of our plug-ins have a saturation component. In most cases, it’s baked in. We carefully model analog circuits. Analog circuits add harmonic distortion. If you crank things up a bit, the circuit starts becoming non-linear and that’s saturation. Crank it up more and it's plain-old distortion.

The Pawn Shop Comp has multiple elements that add harmonic distortion/saturation: there’s a tube preamp, transformers, an FET style compressor (the 1176, with its .5% THD is an FET unit) and the Operating Level knob on the back. The Pawn Shop was designed to replicate a vintage tube analog console channel with a compressor strapped across it.

The Amplified Instrument Processor’s Proprietary Signal Processing feature is there to add three different flavors of harmonic distortion/saturation, depending on its settings. And if you crank up the input a bit, the AIP will saturate in a very analog circuit kind of way. And then there’s the EQ on it, which is emulating a tube equalizer off a 1950s German film mixing console, so some transformers and tubes in the signal path, too.

The Talkback Limiter and the Echoleffe Tape Delay both add lots of saturation if you hit them hard. The TBL adds a FET kind of thing—an analog console vibe, while the ETD does the tube and tape thing.

The Puff Puff mixPass is hard to describe, but what it basically does is add in harmonics using math in a process called Waveshaping. If one reshapes the wave, one is, by definition, distorting it, so you can think of the Puff Puff as a saturator, albeit a special one. Waveshaping is also used on the El Juan Limiter—flip around to the back panel. Finally, the Pumpkin Spice Latte can be thought of as a saturating compressor with additional reverb and delay features.

Lesson: An analog approach to Saturation

An analog approach is to use minimal amounts of saturation all over the mix, turning your DAW into a virtual model of an analog console.

What might this look like?

Set up a rough mix with nothing on the channels or the buses and do the following:

Start out by adding a mix of Pawn Shop Comps and Talkback Limiters spread across all your different channels. Set thresholds high so these things aren’t applying any compression but signal is still passing through the modeled circuit. On the Pawn Shop, perhaps play around with the different tubes and transformer combinations. Don’t be surprised if you really don’t hear much of a difference. We’re adding saturation in a cumulative process.

I tend to use Talkback Limiters on drum tracks and guitar tracks, and PSCs on bass, vocals, etc. Different kinds of saturation.

Quick note: set all of these things at unity gain so you’re not goosing any of the channels louder.

On an analog console, individual channels feed into submix buses and then into the main stereo mix bus. To simulate this, put Amplified Instrument Processors (AIPs) on the submix busses. The AIP is designed to work across a stereo input. Click on the Proprietary Signal Processor and go around to the back panel and select one of the three different settings, yielding three different types of saturation.

Now, on the master bus, normally we throw on the El Juan and a Puff Puff, but for the purpose of this lesson, put on an AIP—to simulate a stereo bus summing circuit—and follow that with an Echoleffe Tape Delay, but switch the ETD to Tape Saturation Mode, to emulate the saturation caused by mixing down to an analog two-track.

Listen for a bit, then switch off all of the plug-ins and listen. A/B compare a few times. The difference is going to be subtle but it will be there.

In fact, we’re used to hearing artificially high amounts of saturation on songs these days. People are overdoing it, resulting in records that are harsh and chiffy-sounding.

Why not just one Saturator at the end?

Good question: why not just throw a saturator over the stereo master and light the sucker up? You can do that, but you have to beware of Intermodulation Distortion.

I wrote a full article on this here. A short take: saturation adds harmonic distortion, which means additional waveforms are added in, using math, to the original waveform. When you start cramming a lot of different waveforms from different instruments through a saturator, they mix with each other and generate yet more waveforms, some of which aren’t mathematically correlated and sound off and out of tune to our ears. Bad math.

Intermodulation distortion is typically nasty sounding to our ears and also fatiguing. Our ears tire of it very quickly. Go into a restaurant with a shitty sound system and try to eat a burger when there’s a lot of intermodulation distortion.

Using a lot of saturation at the end can sound awful. It might be an effect you want, and I have no doubt a lot of mixers get it to work, but this article is about a more nuanced, analog approach, and more than that, it’s about you getting a deeper knowledge of what is going on, and developing audio engineering skills that set you apart from guys that press buttons without really knowing what is going on.

We want you to really know what you’re doing.

Feel free to write us at theguys@.... if you have questions. We’ll always try to help you out.